Varroa Resistant Bees Get $1 Million In Norway

Published in Bee Culture, May 2020, pages 75 – 77

Dr Melissa Oddie, a Canadian researcher, will continue her research for at least two years based on the Varroa resistant bees with Terje Reinertsen in central Norway. Her doctoral dissertation was based on research with these bees. The Norwegian authorities have allocated $ 1 million (NOK 8.5 million) for this research.

February 21-23 the commercial beekeepers in Sweden (Biodlingsforetagarna) had a conference in Sunne in western Sweden close to the Norwegian border at the newly built hotel Selma Spa. It was fully booked. Beekeepers from Sweden, Norway and some from Finland were listening to Terje and Melissa and many others, from the University of Agriculture in Sweden (SLU), from Belgium and Canada to mention a few. Sunne is the place where Selma Lagerlöf lived, a famous author, the first woman to get the Nobel Prize in literature.

Dr. Melissa Oddie and Terje Reinertsen in Sweden.

Dr. Oddie discovered a salient trait in Terje Reinertsen’s bees which expresses itself in that bees uncap pupae in which there are mites and recap them again without damaging the pupae. This apparently interferes with the mites’ reproduction. The characteristic that is otherwise very much in focus today is called VSH (Varroa Sensitive Hygiene). Here, the bees remove pupae that are invaded by mites (mites that have offspring). VSH is not a prominent feature of the resistant Norwegian bees.

Visit in Norway

In the Fall of 2019, my wife Gunvi and I visited Anita and Terje Reinertsen. They don’t have a lot of suitable agriculture land for growing crops in Norway so they use every little piece of land possible to grow food. Quite steep slopes had recently been harvested. Norway is no longer Sweden’s little brother as it’s been for many years. It’s the big brother now, with oil and gas and Varroa resistant bees!

Anita and Terje Reinertsen

The Varroa resistant bees

Some years ago, researchers began to be interested in a population of Varroa resistant bees in Norway around Terje Reinertsen. The important thing is that you don’t have to treat them at all against the Varroa mite, and they are therefore not treated. The mite population in a hive of Terje can vary during the season. His bees havn’t been treated for about 25 years. It was about the time when the mite came to Norway. When I became aware of this, I wondered why we hadn’t heard or read more about his bees during these many years.

Now there has been some exciting research reports from the works of Dr. Melissa Oddie and her coworkers.1,2,3,4 Research on these bees was the basis for her doctoral dissertation. Since then, articles and reports of the bees of Terje Reinertsen have been published.

He has been focused on developing a stock of Varroa resistant bees since the mite began to create problems in Norway. And he has done that together with beekeepers in his vicinity. In April 2019, he was one of the speakers at a conference in southern Sweden on healthy bees that do not need to be treated against parasites and diseases, and how to get there. Melissa Oddie participated, together with several other speakers including also Kirk Webster from Vermont. And now in February 2020 he and Melissa Oddie were speaking in Sunne.

Varroa in Norway

In 1994, the Varroa mite had made its presence so well known among beekeepers in Norway that it was decided that bee colonies had to be treated against the mite. The central association took help from countries where they had had more experience of the mite. Among other things, it was recommended to use ”Krämerplatten” that evaporate formic acid in the bee colony.5

Terje listened carefully to the advice and treated his bees in the recommended way in the Autumn of 1994. He lost 70% of his colonies in the Winter of 1994-95. Other beekeepers also lost about the same amount of beehives. Several lost 100%. Spring treatment with formic acid was then mentioned as an additional alternative to save colonies that survived the Winter. Then fewer holes in the plastic around the formic acid soft board plate were used so that the evaporation speed would not be so high.5 Terje applied this method to the survivors.

Decision not to treat

After analyzing the results of all the treatments, Terje and a some other beekeepers concluded that if you were to loose so many bee colonies after treating, you could just as well not treat, because you didn’t lose more colonies if you didn’t treat.

At that time, little was known about the importance of the balance between all different types of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, and other types of microbes) for the immune system. Such an ecological system of microorganisms in and on a living being is called a microbiome. For example, we humans have about 2 kg of microbes on and in us. Without them we die.

Microbiome and epigenetics

The microbiome6 is now a hot topic in research, even among bees7. The microbiome will become unbalanced if chemicals in sufficient quantities affect the bees.8 Defense against harmful microbes is weakened, for example against pathogenic viruses.

Another hot topic in research is epigenetics.9 Changes in how genes in the DNA are used, in kind of a contrast (or rather complement) to how the composition of the genes in the DNA is changed through breeding (natural or beekeepers).10 Changes in the environment create changes in the DNA so that some genes are turned off and others turned on.

Purchase of never treated bee colonies

In 1995, Terje compensated for his colony losses by purchasing about 35 bee colonies. These came from an area where the Varroa hadn’t yet arrived to, so these colonies had never been treated against Varroa. Some of these colonies were splits raising new queens of their own. The new colonies developed well and wintered successfully. These were more in number than those that survived Varroa and formic acid.

In the Winter of 1995-1996 and onwards, the losses were again about normal, five to 10 %, despite the lack of Varroa treatment.

Because of the large losses of bees for many beekeepers in the winter of 1994-95, the reinvasion of mites was not a problem for Terje’s bees. He also started at once with the simple breeding concept he has followed through the years since. He focused in various ways to identify the worst and the best bee colonies when it comes to keep down the mite population and being resistant to viruses.

Terje Reinertsen shows a split in September, grown in strength to be ready for Winter and well fed.

Breeding strategy

Today Terje Reinertsen doesn’t estimate the varroa level in his colonies. He doesn’t care about varroa mites anymore. Others have though made estimates. And it seems the Varroa levels mainly is 1-3%, with some exceptions at a higher level. The interesting thing is though that no signs of virus damage could be seen.

His main traits for selection are

1 – Good temper

2 – High egglaying capacity

Every year he replaces the queens in the worst 30 % of his hives. They are today about 250. Once they were 350. He is in his retiring age, but he’s working all days. If not with bees, he’s hunting or fishing.

Among the best 10 % of his hives he checks the very best. Good hives are of course also giving a good enough crop. He breeds queens from several of these. He does not regularly replace queens who have grown old. Only when the bee colonies are bad, whether the queens are young or old. Colonies in the mid range (and the best) are allowed to replace their queens themselves. Young queens are mostly mated in the center of an area where many good colonies of somewhat different heritage are kept. This type of mating system you can call population mating, actually the old type of line breeding where all bees in an area could be called a line.

I remember Steve Taber explained what a line really was at the Bee-85 conference in Sweden many years ago. This could be likened with a kind of closed population breeding. In this way, high vitality, good harvest and genetic variation are maintained.

Terje wasn’t sure it was sufficent with the buckfast variety of bees he had initially, so he tried other buckfast types and some other varieties of bees. Today, Terje’s bees could simply be called Terje bees.

Comb foundation

Terje got smaller cellsize wax foundation from Hans-Otto Johnsen, a beekeeper colleague. Shortly after the year of 2000 he reduced the cell size to 5.1 mm, then to 4.9 mm. Now he is in the process of setting up his own, almost commercial equipment for manufacturing wax foundation.

A small mini mating nuc with three mini frames. When the queen is egglaying, Terje harvests it and introduces it in a colony that needs a new queen.

Establishment of another Varroa resistant strain

Ten years ago he acquired 14 Norwegian carniolan queens mated in an area with only carniolan bees in Norway. These queens were introduced to splits from Terje bees. The splits were placed with a beekeeper about 60 km from Terje, isolated from other bees. Today, the 14 colonies have grown into a population of about 100 bee colonies.

All new queens (and splits) come from the group and mated in its area. These colonies have never been treated against varroa. There have always been low winter losses in this group, which has become kind of a stock, a resistant stock. Maybe you can do it this way if you want to produce a Varroa resistant bee stock of a bee variety other than Terje bees.

Terje queens in a different environment

A number of years ago, Terje queens were purchased to some universities in Europe. From Switzerland I have heard results how they managed. They were introduced to colonies of local bees managed in their traditional way. After the introduction of Terje queens, these colonies were not treated against Varroa, and they managed well.

Active in the bee association

Terje has always helped beekeeper colleagues and beginners. He has held beginner courses for many years. And he has helped them with splits and new colonies. He has been the chairman of the local association for 20 years and vice president of the district association for many years. Once a month from April to September, the local association has a club meeting in his garden. There are gathered in average 30-35 people.

The Terje stock

There are now 1500-2000 Terje bee colonies in Norway. There are about 100 beekeepers having these bees and they do not treat against Varroa. Most of these have their bees in the area where Terje lives, 20 minutes north of Oslo, the capital.

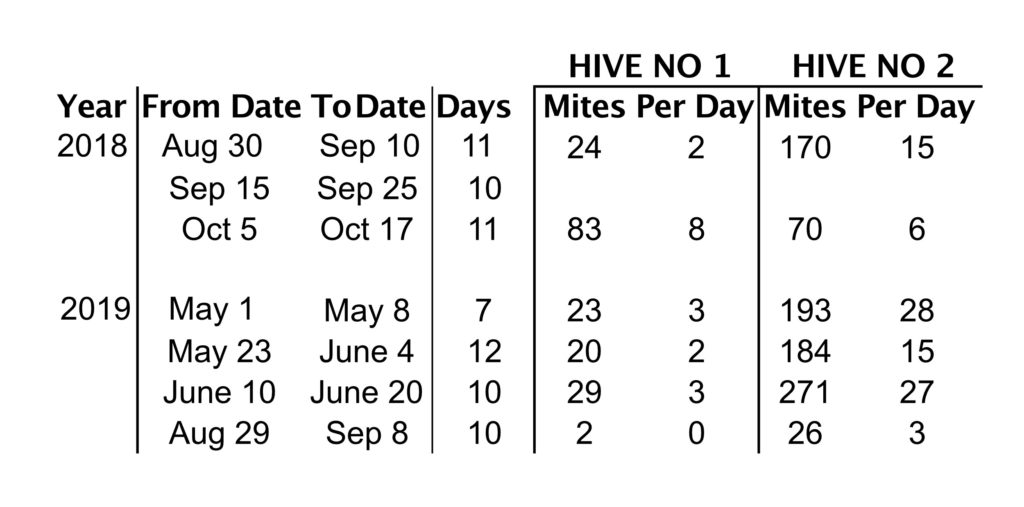

One of these beekeepers, I call him Tim (his name is something else), has eight colonies and lives on the outskirts of the Terje area. There are many bee colonies other than Terje bees around him. The closest is 200 meters (yards) away. Tim has done a small measurement study on the daily natural down fall of mites during a season. It varies during the season and although from some colonies it can be quite big in May, it is low at the end of the season.

References

1. Oddie, M.A.Y., Dahle, B., Neumann, P. 2017. Norwegian honey bees surviving Varroa destructor mite infestations by means of natural selection. PeerJ 5:e3956 – https://peerj.com/articles/3956

2. Oddie, M.A.Y., Dahle, B., and Neumann, P., Reduced Postcapping Period in Honey Bees Surviving Varroa destructor by Means of Natural Selection, MDPI: Insects 2018, 9(4), 149 – https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/9/4/149

3. Oddie, M., Büchler, R., Dahle, B. et al. Rapid parallel evolution overcomes global honey bee parasite. Sci Rep 8, 7704 (2018) doi:10.1038/s41598-018-26001-7 – https://rdcu.be/bZasw

4. Oddie, M.A.Y., Neumann, P. & Dahle, B., Cell size and Varroa destructor mite infestations in susceptible and naturally-surviving honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies, Apidologie (2019) 50: 1. – https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-018-0610-2

5. A piece of soft board, drenched in 250 ml 85% formic acid, 15x17x1 cm in size, put in a tight plastic bag with 2 x 10-15 of 15 mm round holes in the plastic for evaporation, described here. – https://wiki.bienenzeitung.de/index.php?title=Kr%C3%A4merplatte

6. https://golden.com/wiki/Microbiome

7. https://mbio.asm.org/content/7/2/e02164-15

8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1314923110

9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigenetics_in_insects

10. https://www.whatisepigenetics.com/the-epigenetics-of-honeybee-memory-offers-a-glimpse-into-our-own-minds/ ;https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2016.00082

Very interesting article. I wonder how these colonies would fair in other climates and regions? Seems these strains of bees are naturalized to their surroundings? Here in Maryland, most bees suffer from malnutrition or a lack of nectar habitat in summer. Many colonies start fine in spring, then after June the summer dearth starts to destroy moral and the health of the bee colony declines rapidly even despite treatments. Our state failure rate is 60% or higher in many cases.

In this article I tried to avoid making any comments on how this resistance could have arisen. There is a key for understanding this I think. His bees have never been treated against the mite, that is, no chemicals ever to fight the mite has been put in the colonies, at least in the very big majority of them. In 1995 the mites and bees with him AND others had NOT a higher amount of viruses in them as is the case today. So his bees could take a higher reinvasion load of bees from his neighbors and mites that these bees carried, or mites that his bees picked up when silent robbing them.

So normally when you breed queens from such a colony and introduces into local colonies in an area with virus filled mites and bees, which is the case in most areas, colonies developed from such queens wouldn’t fight the mite situation as good as in virus low areas. Maybe, because Terje has had his bees during this many years, epigenetic changes may have taken place with the mite present in the colonies so that eventual epigenetic changes could have taken place and established themselves. These epigenetic changes may have made the queens reared so vital in managing where mites and virus may be a threat that their colonies may handle a situation they couldn’t have handled say for example just a few years later than 1995. That would have been the explanation why queens introduced in Switzerland handled the situation well without treatments. You know even if most colonies of Terje bees show a low varroa level, at times the varroa level can be close to 8 % without any concern.

Concerning malnutrition some of your colonies made it, 40 % of them. Maybe that can be a base for selection for a stock that can handle that situation you describe. Maybe you can start experience a somewhat better survival every year. I once had a 50 % loss during two years (many years back now before the time of the mite) due to so called concrete honey (honeydew of a certain type from fir trees). I cried that 50 % had died, but some years later I realized that 50 % had survived the concrete honey and my stock had developed into a much harder stoch managing under well under difficult situations.

I have to point out here why it is so critical that Terje’s bees never had been treated (the colonies he bought in 1995 that never had been treated with chemical against the mite) is because these colonies had their microbiom intact so that viruses were hold back from developing by other microbes in the microbiom. That is why african bees could develop varroa resistance in so few years, well you can say already from when mites arrived, as even if mite level was high, viruses didn’t develop. As time went by, the varroa level became lower and lower until it seems to have leveled out at 1-2 %. Both due to true genetic changes AND epigenetic changes (genes turned off and others turned on) which have been well established during several generations. That’s what happened to the Italian bees on Fernando de Norhona, http://www.elgon.es/diary/?p=1121

Dear Erik,

very glad to notice that you post something again. It is always a pleasure to listen to someone with such big experience in the area of resistant bees, both from the practical point of view and with the scientific background. Although the latter maybe not that important (at least not in this area), as the example of Terje illustrate.

First of all it is nice to hear about examples in Europe that confirm it is possible to keep bees without treatment and earn Money as well. I remember that you have mentioned Terje sometime ago and I’m glad to hear that he managed his bees succesfully by his own strategy and therefore the numbers of such beekeepers like you and Terje are growing that are able to do so.

To take up your point that it is important to allow bees to adapt on challenges like mites by an intact microbiom: I think this is in line with a lot of your earlier blogpost that cover different measures, like clean wax, clean treatment (if at all, like sugar powder etc) and maybe clean environment.

Actually this is something what I try to avoid as much as possible (but I have never achieve this for 100%, as untouched or better to say not affected areas, that meet the other criteria as well are nearly impossible to find anymore), to get away from agriculture that overuses chemicals to fight against, insects, bacteria and fungi, as too often I realize negative effects on bees.

The other point which I learned in your Blogs 🙂 is, that mating strategy is important as well. If you can control this to some point, you will succeed. If too many beekeepers are around you, which all treat you end up diluting your resistance traits to often.

I tried different mating strategies like stress breeding (mating very early or very late in the season) to go for drones of hives that are vital in the end of the season (when mite pressure becomes very high) to bypass this. But this needs several years, lot’s of trials and focus which is hard to achieve as a hobby bee keeper.

But anyway, at least no chemicals get into my hives and I’m able to collect some honey and propolis and have some fun with it.

Best regards,

Rüdiger

Have you tried so called moonshine mating. It’s not a proper name. You can put selected capped drone frames above a queen excluder with an opening that is closed most of the time. But you have to open it every day in the afternoon when drones in other hives have stopped flying so no drones enters here. The drones have to go to the bathroom every day. About five o’clock in the afternoon a day you want your queens you mate you do the same. And so a number of days until they are mated. The mating nucs you open for mating at the same time when the queens are 7 days old.

Yes I considered that as well, some time ago, but found that too complicated. Of course a few hives are directly at my home, so that would be doable. However, as I’m a hobby bee keeper and have a full time job, I prefered the stress breeding option. So far I have made some positive experiences, although not statistically save, as I have not tested that in bigger numbers.

Plus the last 2 years have been unusually dry and hence seasons have been difficult, with not too much strong hives in September….

So it all takes a bit long…

To come back to positive experiences: 2 times I had very late matings in October and both times queens seem to be more resistant than the mother. Interestingly, one times only Buckfast drones have been successful and the next time only the black bee drones (Apis mellifera mellifera) have been successful. Hence, it seems that this is really a selected mating…

BTW wish all the best for this season Erik!